Grinding and Testing of Telescope Mirrors – Part 4

Tech info | July 19, 2022

Testing the mirrors

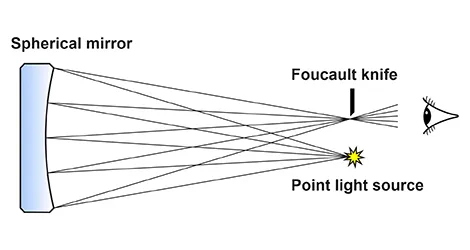

The telescope making dates back to the time of Galileo and Newton. For a long time, opticians did not have a reliable method of checking the quality of optical surfaces. Only in the 19th century, with the development of the wave theory of light, the methodology of testing the optical parts begins to improve. In 1858, the French mathematician and inventor Leon Foucault proposed a method known as the Foucault knife-edge test, in which a point light source is placed near the center of the mirror's curvature along with a rectilinear opaque blade touching the light beam [12][13]. Depending on the shape of the converging wavefront, a picture of alternating dark and light sectors is observed, visually projected on the mirror, and carrying information about the deformations of the optical surface. Foucault's method provides only a qualitative assessment of mirror aberrations without adequate quantitative measure, so the results are difficult to analyze. However, it still remains an essential tool in optical manufacturing, used by amateurs and professionals as another reliable quality check. Among its most important advantages is the extreme simplicity of the equipment, and hence its negligible cost.

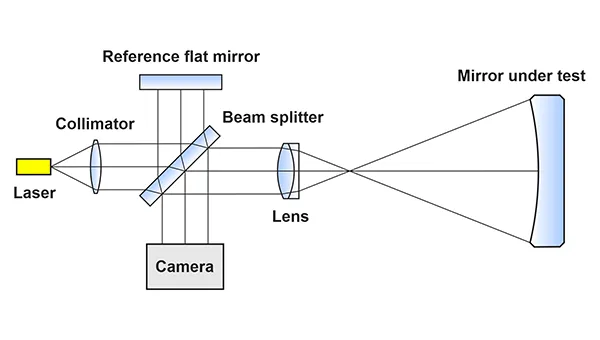

Another group of methods, until recently mainly used by professionals only, but in recent years also by more and more amateurs, are the so-called interferometric methods. As their name indicates, they rely on the physical phenomenon called interference, in which two wavefronts, reference (without deformations) and working one, obtained after interaction with the optical system, are superimposed, resulting in an interference pattern showing the phase differences between them. The light source is a highly coherent and stabilized laser. The picture is observed with a digital camera and processed for subsequent analysis. Among the most used configurations in optical control are the interferometers of Bath, Twyman-Green, Fizeau, Michelson, etc. [3][8]. The main advantage of these methods is the high accuracy and the possibility of precise quantitative analysis of the tested surface using specialized software. On the other hand, they require expensive and delicate laboratory equipment, which is difficult for many amateurs to access and remains widespread mostly in professional workshops.

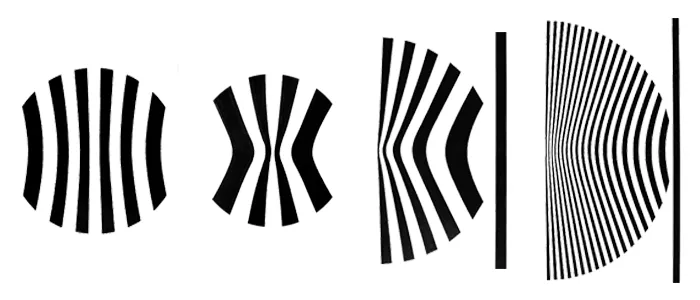

Here we will describe one of our methods, developed and successfully applied in our practice. It further improves some ideas proposed over the years by many authors related to optical control and telescope construction. In 1922, the Italian physicist Vasco Ronchi proposed, instead of a Foucault knife, the use of a grating (not to be confused with a diffraction grating) of alternating black and transparent, straight bands with a density of 5 to 10 l/mm placed in the light beam, near the center of curvature of a spherical mirror [10]. In this way, any error on the optical surface would distort the image of the lines, thus making the diagnostics very convenient and easy to observe. On an ideal sphere, the straight lines of the grating are projected as straight lines on the mirror. The method is known as Ronchi gratings. Many manufacturers on the market today are offering high-quality gratings.

Ronchi's method is ideal in the case of a spherical surface, but in the case of an aspherical one, the bands are distorted in a complex way. Therefore another solution is needed. It consists in curving the lines in advance so that when the surface acquires its exact aspherical profile, the image of the grating on the mirror consists of straight lines, as in the case of an ideal sphere. Similar approaches have been developed by various authors [4][5][6][9][11] and are known as null-tests.

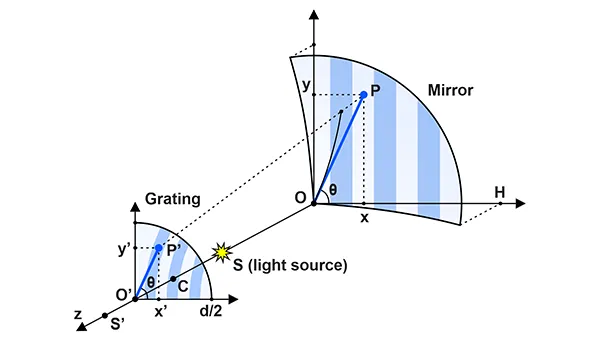

Our method is essentially also a null test. It consists in calculating the exact shape of the grating bands for aspheric surfaces of rotation with different eccentricities and distances along the optical axis of the point light source relative to the paraxial center of the curvature. Our approach is based on the so-called ray tracing method without accounting for the diffraction. The latter is possible because the slits formed between the grating lines are large enough compared to the wavelength of light, so diffraction is not observed. The figure below demonstrates the geometric formulation of our method.

Here point C is a paraxial ceneter, S is a point light source, offset from point C by a distance δ = |CS| towards the mirror and point S' is its paraxial image. The grating is located at a distance Δz = |O'S'| from point S', in the positive direction towards the mirror.

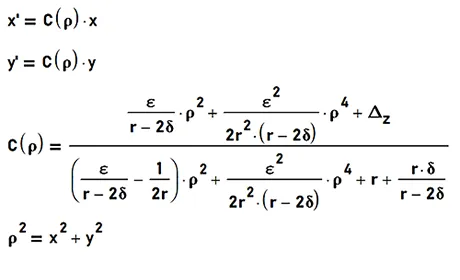

Without going into details about the derivation of the next equations, we will present the final result, which shows the relationship between the point P' with coordinates (x', y') in the grating plane and its image point P with coordinates (x, y) on the mirror. The relationship is given by the following:

Here ε is the eccentricity of the surface, as for a sphere ε = 0, for an ellipse 0 < ε < 1, for a parabola ε = 1, and for a hyperbola ε > 1. r is the paraxial radius of the curvature, δ is the distance of the point light source from the center of the curvature toward the mirror, Δz is the distance between the grating and paraxial image of the light source, which is located at a distance r⋅δ / (r - 2δ) behind the center of the curvature. Accordingly, the diameter of the grating is d = 2⋅C(H)⋅H, where H = D / 2 is half the diameter of the mirror. Moving the point source along the optical axis towards the mirror allows the grating to be positioned conveniently behind it, remaining on the axis. That avoids off-axis aberrations during testing, which is very important for fast mirrors.

By setting the coordinates of the points in the mirror plane and using the above equations, we can determine the coordinates of their corresponding images on the grating. For example, by fixing x and changing only y, we will form a pattern consisting of vertical straight lines, as in the Ronchi gratings and as shown in [4][6][9]. If we change x and y in such a way that concentric equally spaced circles appear on the mirror, we will form a radial grating of concentric circles again, but with different spaces between them. A similar approach is demonstrated in [11]. You can use our online Ronchi gratings calculator to compute different types of null-test gratings for aspherical mirrors.

For example, for an F2 parabolic mirror with a diameter of 250 mm, the above formulas provide an accuracy of the grating coordinates no less than 10-3 mm (1 µm). As the relative aperture of the mirror decreases, the accuracy improves. Among the advantages of our approach are its low computational complexity, ease of use, and negligible cost compared to interference methods. The gratings calculated using the above equations can be printed by lithographic technology or printed in a large size and then photographed in final size on a contrast fine-grained diapositive film.

Epilogue (instead of conclusion)

Telescopes have always been my (BB) passion since my earliest childhood. And not just to observe the world through them, but to make them. That is how I began to develop this activity in a more professional manner when I was a student at Sofia University at the beginning of the 90s. Because the times were critical, the Berlin Wall had just come down, the political system was changing, and the impact on all of us was devastating. The entire state industry, together with the know-how created until then, was completely destroyed, and there wasn't even a word about creating a new one. That was accompanied by mass emigration, unemployment, hyperinflation, poverty, and hunger. We had barely heard about the Internet and e-mail, the computers were an expensive exotic that many of us couldn't afford, and access to modern scientific journals and publications was an almost impossible dream. But in spite of all this, I was young and had enormous enthusiasm. I was full of hope.

While I was engaged in telescope making, I had to construct all the machines and tools for the manufacturing and optical control of the mirrors by myself. Since I had no access to scientific journals or articles, I began to develop my own technological know-how, especially in the case of fast aspherical surfaces. The work was everything to me, so I enjoyed it full of passion. At that time, I didn't have a computer yet. I did all the calculations either by hand or with the help of a small Casio fx-P401 programmable calculator that I had prudently bought during my student years. It turned out that, independently of the other authors, I had rediscovered null-test methods, but I found out about this years later when I already had access to the Internet. That's why I haven't officially published anything related to my developments so far. And so, almost nine years of my life passed. During that time, among many other things, I succeeded in producing nearly two dozen mirrors with various apertures and f-numbers.

At one moment, I decided to contact the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences as an official representative of the scientific community in my country and seek some understanding and support. Moreover, the theoretical and practical material I had accumulated at that moment was pretty enough for a Ph.D. dissertation. My idea was to create a small development unit, a laboratory, or something similar, where I could continue to improve the technological know-how and experience acquired during these years. My secret idea was that in this way, native science would be able to have a small team of specialists in such an interesting but, unfortunately, an undeveloped scientific field in our country. A compact manufacturing facility for making small to mid-sized aspherical optical components would bring both revenue and international prestige. But as they say – yes, but no.

Instead of the understanding and support I was seeking for, I encountered hostility and dislike [1][2]. Now, after more than two decades, I think that maybe it was meant to be. That's the way the world is. New things and ideas have a hard time making their way. Or, maybe what I've been doing all these years is not worth it at all and has no value? Who knows?

Either way, I was forced to stop my pursuits and move on. Now, I don't regret it. Life should always continue!

You can read more about the history of telescope making in the first part of our series. Learn more about grinding of optical surfaces and polishing and figuring the mirrors.

Reference

- Abbot A.

Science fortunes of Balkan neighbours diverge

, Nature, Vol. 469, 2011. - Abbot A.

Funding protest hits Bulgarian research agency

, Nature, Vol. 491, 2012. - Born M., Wolf E.

Principles of optics. Electromagnetic theory of propagation, interference and diffraction of light

, Pergamon Press, 4th Edition, 1968. - Hopkins G., Shagam R.

Null Ronchi gratings from spot diagrams

, Applied Optics, Vol. 16, No. 10, 1977. - Malacara D.

Geometrical Ronchi test of aspherical mirrors

, Applied Optics, Vol. 4, No. 11, 1965. - Malacara D., Cornejo A.

Null Ronchi Test for Aspherical Surfaces

, Applied Optics, Vol. 13, No. 8, 1974. - Malacara D., Cornejo A., Murty M.

Bibliography of various optical testing methods

, Applied Optics, Vol. 14, No. 5, 1975. - Malacara D.

Interferogramm analysis for optical testing

, Taylor & Francis Group, 2005. - Mobsby E.

A Ronchi null test for paraboloids

, Sky & Telescope, November, 1974. - Ronchi V.

Forty years of history of a grating interferometer

, Applied Optics, Vol. 3, No. 4, 1964. - Terebizh V.

A new Ronchi null test for mirrors

, Sky & Telescope, September, 1990. - Максутов Д.

Изготовление и исследование астрономической оптики

, Наука, 1984. - Сикорук Л.

Телескопы для любителей астрономии

, Наука, 1982.