Stellar Aberration and Detection of Absolute Motion

Sci report | July 25, 2022

Stellar parallax and aberration

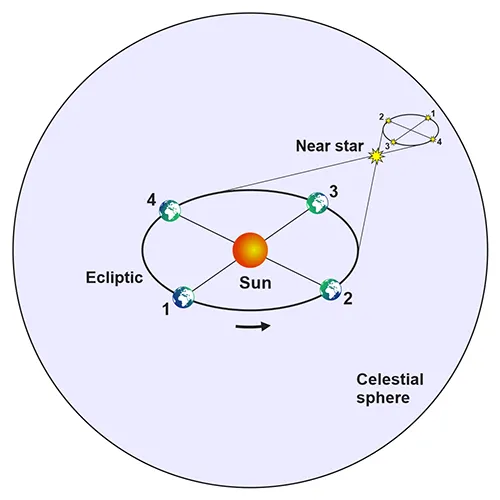

In classical astronomy, the phenomenon called stellar parallax is well known. It is the apparent angular displacement of nearby stars relative to distant space due to the projection of the Earth's orbit onto the celestial sphere. As seen by an observer on the Earth, during a year, the star draws in the sky a tiny ellipse, representing the projection of the Earth's orbit. In the case of stars near the ecliptic, the ellipse collapses into a single line. The magnitude of these projections depends on the distance to the observed star. Therefore, the parallaxes are important in astronomy because, using them, we can determine the distances to the stars. We have all seen this phenomenon in our daily lives. Remember how the clock hand changes its apparent position relative to the numbers on the dial behind it as the angle at which we observe the clock changes.

In 1726, the British astronomer James Bradley decided to study this phenomenon. He chooses γ Draconis as a suitable star because it is bright enough, does not set during the year, and passes through the zenith point for an observer in London. Bradley mounted a small telescope in a vertical position aimed at the zenith, fixing it to the chimney stick in the house located near the town. The following year, the observations are carried out regularly. To his great surprise, he noticed that the apparent position of the star changes during the year but in a completely different way than expected [2]. The truth is that using the technology of that time, stellar parallax was impossible to observe. The first successful measurements succeeded a century later. Bradley, however, discovered a new phenomenon called stellar aberration. It is due to the movement of the Earth and the finite, albeit very high, speed of light.

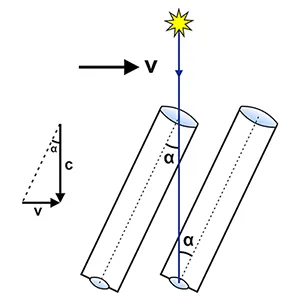

Let us imagine a vertical and stationary hollow cylinder and let a small ball falls into the center of its opening at the top. Then, because the cylinder is stationary, the ball will continue down and hit the center at the bottom. Let us now imagine that our cylinder is moving in a horizontal direction. Then the ball will deflect and no longer fall into the center of the bottom. The moving cylinder must be tilted in the displacement direction to keep the ball hitting the center. Similarly, a light ray from a star hitting the center of a telescope objective travels the distance to the eyepiece in a finite amount of time. During this time, due to the motion of the Earth, the telescope has traveled some distance, and the ray has apparently deviated from the center of the eyepiece, as shown in the figure below. Thus, the image of a zenith star describes a small circle around its mean position during the year. Bradley measured the maximum deviation α and found it to be 20.5 arcseconds (roughly 1/175th of a degree). For stars not passing through the zenith, the deviation is in the form of an ellipse with the same major semi-axis, as for stars in the ecliptic, the ellipse collapses into a straight line.

The Earth travels in its orbit around the Sun with an average speed v approximately equal to 30 km/s. The light speed c, on the other hand, is 300,000 km/s. Then, the angle α at which the telescope must be tilted so that the image of the star falls onto the center of the eyepiece is:

α ≈ tan(α) = v / c ≈ 20".5

With the discovery of stellar aberration, Bradley proves the validity of the Copernican model of the solar system. To this day, the phenomenon is one of the strongest arguments supporting the theory of the luminiferous aether – a stationary immaterial medium filling the universe, through which electromagnetic waves and light propagate [4].

Almost a century later, in 1818, Augustin Fresnel developed and supplemented the ether hypothesis from the wave theory of light point of view [3], predicting that the stellar aberration would not change if observed through a telescope filled with a denser transparent medium other than air. The latter was confirmed in 1871 with the experiment of Airy, who observed stellar aberration using a telescope filled with water [1]. The modern explanation of the phenomenon follows the Special Theory of Relativity and is unnecessarily complicated [5]. The theory uses mathematical technics through which it can explain everything in any possible way, without even the presence of common sense. We will not be considering its speculations.

Stellar aberration and absolute motion

The question naturally arises whether we shall be able to use stellar aberration to measure the absolute motion of our world relative to the stationary ether. Let us assume that the entire solar system is moving at a constant velocity in some direction relative to the surrounding space. Therefore, the motion of the Earth along its orbit, which makes possible the observation of stellar aberration, is a variation superimposed on the constant absolute velocity of our general movement, which cannot be measured in this way.

The question then remains whether it is possible to detect our absolute motion relative to the ether by observing an aberration from a local light source. To find out the answer to this question, read about some of our first-order experiments done over the years.

Conclusion

The phenomenon of stellar aberration is the most undeniable argument in support of the idea of a motionless etheric ocean filling space and through which our material world exists. In modern science, this phenomenon is undeservedly marginalized and reduced to an insignificant technical detail to be accounted for in astronomical observations without emphasizing its fundamental importance. Despite all this, a fact is a fact, and stellar aberration remains one of the most important discoveries in astronomy and science.

Reference

- Airy G.

On a supposed alteration in the amount of astronomical aberration of light, produced by the passage of the light through a considerable thickness of refracting medium

, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 20, pp. 35-39, 1871. - Bradley J.

A letter from the reverend Mr. James Bradley savilian professor of astronomy at Oxford, and F.R.S. to Dr. Edmond Halley astronom. reg. &c. giving an account of a new discovered motion of the fix'd stars

, Philosophical Transactions, Vol. 35 (406), No. 1727, pp. 637–661, 1727. - Fresnel A.

Letter from Augustin Fresnel to Francois Arago concerning the influence of terrestrial movement on several optical phenomena

, The General Science Jurnal, 2006. - Janssen M., Stachel J.

The optics and electrodynamics of moving bodies

, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Preprint 265, 2004. - Walker G.

Astronomical observations. An optical perspective

, Cambridge University Press, 1987.