Experiments of First Order Using Photodiodes

Sci report | July 22, 2022

The luminiferous aether

Until the beginning of the 20th century, the concept of the existence of the so-called luminiferous aether dominates physics. Aristotle calls it the Quintus essence (fifth element) and points out that the other four elements that make up the material world – fire, air, water and earth – are made of aether. Notice the similarity with the modern concept of the four aggregate states of matter – plasma, gas, liquid and solid. Unlike the other four elements, we (the human beings) have no sense of aether. That is why proving it by a physical experiment is so difficult. That is quite understandable, considering that all modern science is built depending on our sensory experience and the ability to perceive the world around us using the senses with which the Creator has gifted us. Examining concepts not based on our senses takes us out of the natural sciences and into the realm of mysticism and the occult [16].

The concept of the aether began dominating science in the 16th century with the works of René Descartes and Galileo Galilei, reaching its apogee in the 19th century. Virtually all the great physicists of this era believe in the existence of aether. The general paradigm underlying scientific knowledge at the time was that the aether filled the entire stationary universe, and the natural vibrations of this medium represented electromagnetic waves and light. Scientists are convinced that all known interactions between objects in the material world communicate through the aether. The physics of that time engaged with two main tasks, which it tried to solve through this period. First, to determine, through a laboratory experiment, the absolute motion of our globe relative to the static aether medium, and second, to construct a successful theoretical model for this medium. Both tasks remain unsolved. Considering the first task, we should mention the experiments of Arago, Fresnel, Faraday, J. C. Maxwell, Fizeau, Airy, Lorentz, FitzGerald, Michelson, Morley, and many other great scientists of the epoch. In an attempt to describe the aether, the theoretical models of Fresnel, Maxwell, Kelvin, Stokes, and Lorenz should be noticed. After the null results of all the experiments trying to detect the absolute motion of the Earth, and especially the Michelson-Morley experiment [12][13], a second-order interference experiment proposed by Maxwell in 1878, shortly before his death, the concept of the luminiferous aether began to devalue. At the beginning of the 20th century, it was fully denied and forgotten by modern physics.

First or second order?

Before we go any further, let's clarify what the first-order and second-order experiments are. All the experiments mentioned so far have attempted to detect the absolute motion of our globe relative to the luminiferous aether, using some optical or electromagnetic phenomenon. That is quite logical because, according to the beliefs of the time, electromagnetic waves and light represent natural oscillations of the aether medium itself. Let us not forget that in the 19th century, the wave theory of the light prevailed, and therefore the following considerations are possible.

As we know, light propagates in a vacuo, i.e., in a space free of matter, with a speed c equal to 3*108 m/s. In all these experiments, the ratio v/c is taken into account, where v is the speed of our globe in space. If v/c is of the first degree in the theoretical model of the experiment, then we are talking about a first-order. If the ratio is of the second degree, i.e. (v/c)2, we mean a second-order experiment.

At that time, it was well known from astronomical observations that the Earth travels around the Sun at an average speed of 3*104 m/s (30 km/s). Then, the ratio v/c equals 0.0001, i.e. 10-4, while (v/c)2 equals 0.00000001, i.e. 10-8. Clearly, (v/c)2 will be a quantity 10000 times smaller than v/c, so in the second set of experiments, we will have a huge challenge to the accuracy of the measurement setup.

When does the ratio v/c occur, and when does (v/c)2? To answer this question, we must note the following. Even centuries ago, physicists knew that our material world is extremely porous, i.e., the matter consists mostly of empty space, where the mass is concentrated only in small volumes [5]. Even the densest material bodies are like a cobweb

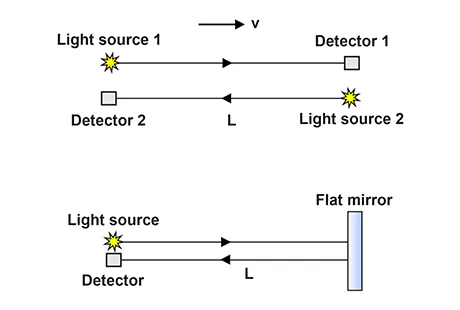

in 3D space. This fact was brilliantly confirmed in the experiments of the British physicist Ernest Rutherford at the beginning of the 20th century [14]. Nowadays, we know that these small volumes of matter are the elementary particles building our world. So, let's imagine, as we travel through the absolute medium with a velocity v, we turn on a light source that propagates with a speed c in the aether, regardless of our motion. Then, for an observer in our moving frame of reference, the speed of light will be c - v if we are moving in the direction of propagation of the light beam or c + v if we are moving against the beam. We then have two basic choices of the light source and detector placement in our reference system, shown in the following figure.

Here, L is the distance between the source and the detector in the first case (top) and the distance between the source (or detector) and the mirror in the second (bottom). In the first case, the time for the beam to travel a distance L will be L / (c - v) or L / (c + v). The difference between these two times Δτ is a function of our velocity of motion v and is equal to:

Δτ = L / (c - v) - L / (c + v) ≈ 2L / c ⋅ v / c

where, after reducing to a common denominator and expanding the expression in Taylor's series [2] in powers of v/c, we have kept only the term of the first degree since the terms of higher degrees are negligible with respect to it. Some first-order experiments are reported in [1][3][9][11][15].

In the second setup, the time Δτ for the beam to travel the distance to the mirror and back to the detector is:

Δτ = L / (c - v) + L / (c + v) ≈ 2L / c ⋅ (1 + v2 / c2)

It can be seen that under analogous transformations as in the above case, the expression again evolves in Taylor's series expansion, but this time the term of the first degree with respect to v/c is zero. Thus, the first significant term is (v/c)2. A classic example of a second-order experiment is the famous Michelson-Morley experiment [12][13].

Our exsperiments

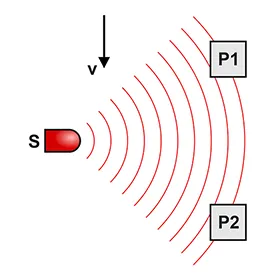

Here we will demonstrate the results of our idea implemented as two separate first-order experiments carried out in 2007. Similar studies were provided by the brilliant Bulgarian physicist Stefan Marinov [10]. We should mention that our idea appeared quite spontaneously and was not inspired by Stefan Marinov's work. The following figure demonstrates the schematic diagram of the experimental setup.

Here, S is the light source, P1 and P2 are two semiconductor photodiodes, and the differential difference in generated photocurrents is amplified and detected. As we travel relative to the ether with velocity v, depending on the direction of the velocity vector, a slight shift of the spherical wavefront emitted by the light source and falling on the two photodiodes should occur. Therefore, a local manifestation of the well-known astronomical phenomenon called stellar aberration should be observed. The last should lead to a difference in the two photocurrents.

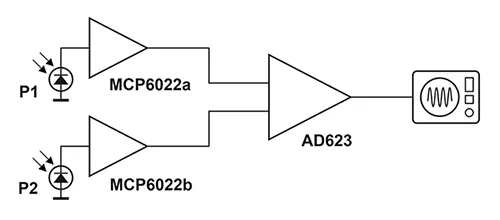

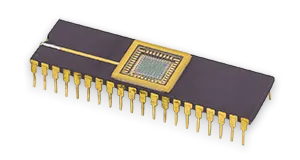

We use a bright red LED with a stabilized power supply as a monochromatic light source. Photodiodes are BPW34, and the operational amplifiers are MCP6022. For the differential photocurrent amplification, we use an instrumentation amplifier AD623. The output signal is observed on the oscilloscope's screen. All circuit parameters are selected so that the signal generated by the desired effect is in the range of several volts and can be recorded reliably. The whole setup is mounted in a shielded metal box.

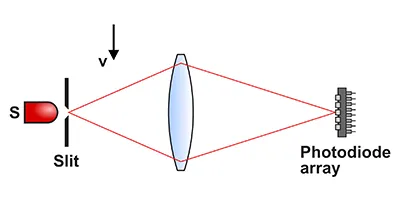

In the second experiment, a narrow slit is placed in front of the LED, serving as a point light source. It is projected by a small lens onto two adjacent photodiodes from an array of 40 semiconductor photodiodes, each with a size of 0.8×0.8 mm. In this way, the spatial coherence of the emitted wavefront is achieved. To register the output signal, we use the same electronic circuit. The schematic of this setup is shown below.

The setups are rotated in different directions in space to achieve a change in orientation relative to the velocity vector v. Only null results were obtained in both experiments. The expected effect of local stellar aberration is not observed.

Conclusion

Of course, the modern explanation for the null result of the experiments would follow Einstein's theory of relativity. But it would be much more interesting to use the concepts of classical physics. In our opinion, the null results follow the hypothesis about the entrainment of the luminiferous aether by moving bodies (aether drag) proposed in 1818 by Fresnel in his letter to Arago [5] and confirmed by the experiments of Fizeau [4], Airy [1 ] and Jones [7][8]. Without going into details, Fresnel's hypothesis guarantees that the absolute motion cannot be detected by a first-order laboratory optical experiment [6].

Reference

- Airy G.

On a supposed alteration in the amount of astronomical aberration of light, produced by the passage of the light through a considerable thickness of refracting medium

, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 20, pp. 35-39, 1871. - Bartsch H.

Mathematische formeln

, VEB Rachbuchverlag, Leipzig, 1984. - Cahill R.

The Roland De Witte 1991 experiment (to the memory of Roland De Witte)

, Progress in Physics, Vol. 3, 2006. - Fizeau H.

Sur les hypothèses relatives à l'éther lumineux

, Comptes Rendus, Vol. 33, pp. 349–355, 1851. - Fresnel A.

Letter from Augustin Fresnel to Francois Arago concerning the influence of terrestrial movement on several optical phenomena

, The General Science Jurnal, 2006. - Janssen M., Stachel J.

The optics and electrodynamics of moving bodies

, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Preprint 265, 2004. - Jones R.

Fresnel aether drag in a transversely moving medium

, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 328, pp. 337-352, 1972. - Jones R.

Aether drag in a transversely moving medium

, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 345, pp. 351-364, 1975. - Marinov S.

Measurement of the laboratory’s absolute velocity

, General Relativity & Gravitation, Vol. 12, pp. 57-65, 1980. - Marinov S.

The "wired photocells" experiment

, Classical physics III, East-West, Graz, pp. 264-270, 1981. - Marinov S.

New measurement of the Earth’s absolute velocity with the help of the "Coupled Shutters" experiment

, Progress in Physics, Vol. 1, 2007. - Michelson A.

The relative motion of the Earth and the luminiferous ether

, The American Journal of Science, Vol. XXXIV, Art. XXI, 1881. - Michelson A., Morley E.

On the relative motion of the Earth and the luminiferous ether

, The American Journal of Science, Vol. XXXIV, No. 208, 1887. - Rutherford E.

The scattering of alpha and beta particles by matter and the structure of the atom

, Philosophical Magazine, Vol. 21, pp. 669-688, 1911. - Silvertooth E.

Experimental detection of the ether

, Speculations in Science and Technology, Vol. 10.1, pp. 3-7, 1986. - Steiner R.

Die geheimwissenschaft im umriss

, Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Dornach, 1985.